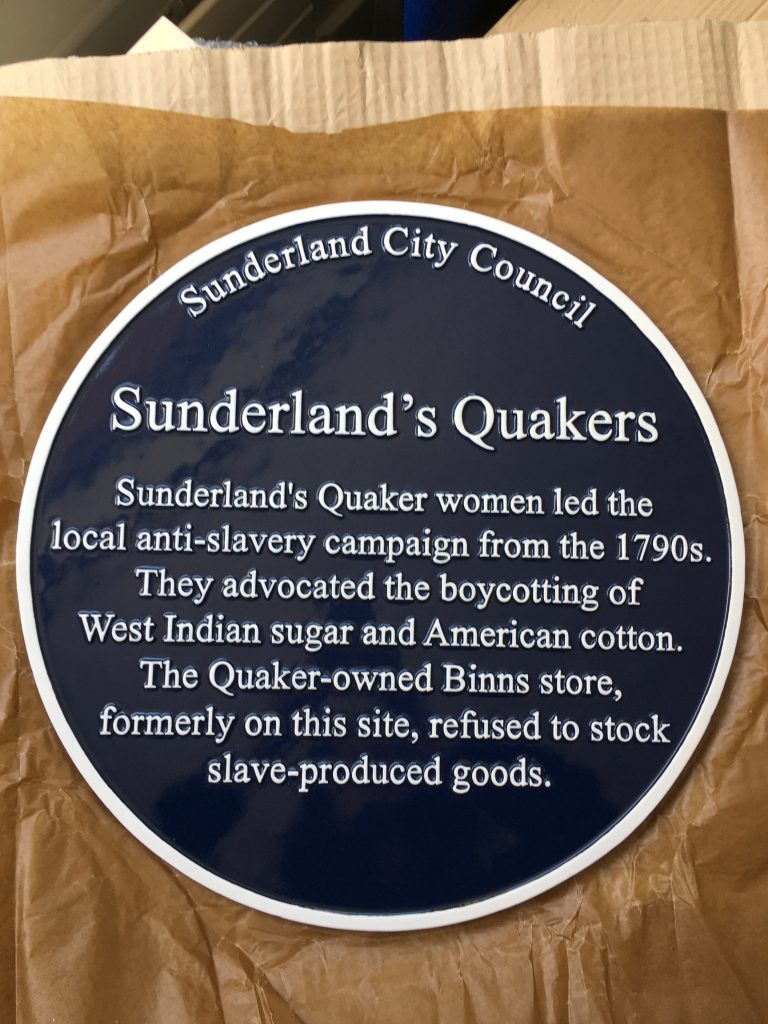

Sunderland Lab building receives a blue plaque to commemorate Quaker women’s anti-slavery activism on June 30.

“Sunderland’s Quaker women led the local anti-slavery campaign from the 1790s. They advocated the boycotting of East Indian Sugar and American cotton. The Quaker-owned Binns store, formerly on this site, refused to stick slave-produced goods.” (Plaque text)

The stories held and told by a building are part of how accessible and safe that building is, and to whom. It is important to reflect on this and understand that, as heritage is used to create feelings of belonging and community, it also signals who does not belong. What stories do we (who is included in this ‘we’?) decide to include in heritage, and which ones are erased or ignored? This happens in formal listing processes, but also in the everyday, in the practices of maintaining and repairing some buildings and not others, in the uncritical reproduction of harmful histories, and the exclusion of histories, narratives and voices.

One of the stories that was largely going untold in Sunderland until now, is about the activism of Quaker women in town. Sunderland Quaker history is intertwined with the abolitionist movement from the early 18th century, and the Sunderland Quakers became particularly well known for one campaign whereby the Quaker shop keepers refused to stock (slave-produced) West Indian sugar. This action followed a push by other Quaker women in the country, such as Elizabeth Heyrick and Elizabeth Pease, who reinvigorated the campaign against buying and stocking products that were produced by enslaved people, to support the campaign for the complete and immediate abolition of slavery as an institution. In Sunderland, this call to action saw many shops change their stock, as well as many women change where they shopped. This was just one of the awareness-raising campaigns that the Quaker women organised!

A blue plaque has now been put up to commemorate these often-forgotten actions led by women. It was put onto the facade of the former ‘Binns Building’, as the Binns family, who owned and ran No. 172/3( Binns drapery and department store) were Quakers, they were also active in the anti-slavery movement, and advertised their refusal to sell “any goods manufactured from cotton not warranted to be free labour grown” giving their customers the opportunity to strike an “effectual blow to the traffic so opposed to the services of religion and humanity” (Moss 2004). So, they were one of those Sunderland grocers who actively refused to stock West Indian Sugar. Although, one has to wonder if circumstances under which the often promoted alternative, East Indian Sugar, was produced, were much better.

So, whilst it is important to remain critical, and keep questioning and reflecting on history, as there are more stories to be uncovered, different perspectives to be addressed, and plaques to put up, and take down, it is also important that this plaque is to women Quakers. Women were excluded from public life, and from property owning, until the latter part of the 19th century. This coincided with the elevation of feminine domesticity throughout that century. The strategies adopted by the Quaker women to raise awareness of the evils of slavery are strategies that we can see are reflecting this context. Household management, and emergent shopping practices, were (and still are) coded as female, and so the boycotting of consumer products can be seen as an innovative and fruitful tactic. The names above the shop doors may well have been men’s, who had priority in inheriting businesses and legal rights in developing them. However, it is women, both as activists and consumers, that led to the increased awareness taking place in the homes of the inhabitants of Sunderland.

The aim of the blue plaque is not to celebrate them as ‘white saviours’ but as to make visible and recognise their role in activism as allies, as is often rendered invisible, and which may inspire women in Sunderland now and in the future!

For more info reach out to Loes Veldpaus (Newcastle University) and Angela Smith (Sunderland University)